Since Lilly reminded me that this site still exists, though in some it's crushed and in some it's staggering, I'll go on.

I just read Kafka's The Trial. Has anyone else read it? What did you think? Here are some thoughts of mine that I'm shamelessly repurposing from another email thread. There are a few references to earlier parts of the conversation, but you should be able to get the gist of it. (The William in here is William Stewart, and the Steve is Steve Lechner, and the Jeremiah is Jeremiah Kelly, for those of you who know any of them.)

This part I wrote when I was about halfway through the book:

"As per The Trial, I kind of agree with you, William, that Kafka is kind of playing with the reader, in the same way that Melville plays with the reader in Moby-Dick. But I don't think that means you shouldn't "take it seriously." My thoughts on this are still inchoate, since I'm still only halfway through the book, but I think it's a lot more than "just a funny story (haha funny in an awful) about the awful impotence K experiences before a huge judicial system." So I'm more with Jeremiah on this one. Jeremiah, I loved your jeremiad on bureaucracy. But I think there's even more to it than just a darkly humorous satire of bureaucracy, even a bureaucracy that your life depends on. I get the sense that he is getting at this crushing absurdity in life. You find yourself on this planet and you have a feeling like there is something you're supposed to be doing, like there is some meaning you're supposed to have figured out; you get the sense that there is something that everybody understands but you, and they expect you to understand it, but when you try to understand it these same people revolt against you, therefore you're stuck in this queer ignorance, and you start to question even yourself, you start to feel guilty about you know not what, you wonder if you're really the crazy one. I don't think I'm articulating it very clearly, and I don't think it can be articulated very clearly. That's why Kafka had to write a whole book to try to articulate it slantwise. And there is much more to the puzzle, like all the women who seem to be constantly helping or hindering K. Why does K. impulsively accost Fraulein Burstner on the night after he is first "arrested" and damn near rape her? I think there is some deep psychological shit going on here. William, you're right, it's not neat and clean, and we're probably not meant to "solve" it like a puzzle, but I can't help but try--the same way that K. can't help but try to understand what he is accused of and what his case means, even though there is probably no answer and the whole thing is just absolutely 100% absurd."

And here is what I wrote after I finished:

"I just finished The Trial on the bus home from work, and wow. Wow. What an utterly bizarre and obscure story. The end caught me completely by surprise; I was not expecting anything so violent.

I have to admit, for the first half or so, I was not that into it, but it got better as it went on--or at least I started reading it more eagerly as I went on. As K. was slowly drawn into his trial, dwelling on it more and more, so I was slowly drawn into it, in parallel. (Not that it was a matter of life or death for me by the end.)

I still stand by what I wrote about it when I was halfway through. But there are so many complexities and things that seem symbolic in this book, I would not attempt a straightforward explication of what it "means." That would only lead me into the same kind of hermeneutic acrobatics and absurdities as the priest demonstrates in his discussion of the fable at the end. I believe there is nothing outside of the text, and Kafka makes that point perhaps better than anyone with this book.

However, as I was reading the book, I couldn't stop thinking about the Court as a symbol for the Church, and this impression only increased as the book went on. That could easily just be what I wanted to read into it. But I think Kafka throws off some definite hints in this direction, especially in the Cathedral scene. On the other hand, the Court cannot simply stand for the Church, in a one-to-one allegorical fashion. If it did, you would have the problem of why there is also a Church (well, a cathedral) and a priest in the book, in addition to the Court. Actually, the priest works for the Court. So the Court is bigger than the Church (or at least than the church). The Court is something universal--it is as big as life itself, or possibly bigger. And besides that difficulty, it seems obvious that interpreting the book in a one-to-one, allegorical fashion is wrongheaded. I don't think the "symbols" in it "stand for" anything in a as the symbols in Orwell's Animal Farm do. Of course, they may have stood for something in Kafka's mind; he may have known what they "meant," or at least had some obscure idea of it. But all we have is the text he chose to leave us with. Still, I don't think trying to to interpret it is a pointless exercise. If anything, it tells you more about what's in your own head than what was in Kafka's. The obscurity of this book is like a Rorschach ink blot; the way you interpret it says a lot about the way you think and what happens to be on your mind at present. So what I said about the Church may very well just be my own addition (although I think Kafka does gives a few teasing hints in this direction).

Perhaps it's not surprising that I felt this kinship between the Court and the Church, since both touch on fundamental questions of life and death, guilt and innocence--they both preside and at least claim authority over the existential questions we must face day to day. So it's almost inevitable that Kafka ended up couching the Court in religious language and imagery. At the same time, though, it must be significant that he chose a secular body, the court, as the ultimate decider of fate, rather than a religious body. It could be that he did this to avoid persecution, but I don't think so. It seems to me that the Court's secular and bureaucratic nature is essential to its meaning, whatever that is.

That's pretty much all I can say about it right now. I still feel in the dark about the function of the various women in the book (I mean, even more in the dark than I feel about the rest of it, which is significantly). Anyone have any thoughts on that?

I remember there was a pretty sizeable chunk dealing with The Trial in this book called Genesis of Secrecy by Frank Kermode, which we read for [Prof. Duttenhaver's] PLS Bible class. It's a fantastic book about hermeneutics, and I can't recommend it enough. It's also fairly short, and one of those books I would describe as "intellectual but not academic." I.e. it doesn't mess around with pedantic details. But it does dwell on significant details. In fact, the whole book kind of turns on the difference between one little sentence found in Mark and Matthew, when Jesus is explaining why he speaks in parables. The book made a big impression on me at the time, three years ago, and I've found myself returning to its many insights again and again since I read it. It's one of those books that never leaves you once you read it (at least for me). In fact, that book is half the reason I wanted to read The Trial in the first place. (Another book that it refers to a lot is Ulysses, which makes me also want to read that a lot.) So I hope to return to that passage and see what it had to say."

-Joey

Hey all,

I am, finally, reading Alasdair MacIntyre's "After Virtue". I can now join Tavs in the "Alasdair MacIntyre Fan Club." The book is fantastic.

At the outset, MacIntyre argues, "Imagine that the natural sciences were to suffer the effects of a catastrophe. Riots occur, labs are burned down, books and instruments are destroyed. Much later, enlightened people try to revive science, although they have largely forgotten what it was. All they possess are fragments; parts of theories; half-chapters from books; instruments whose use is forgotten.

They lump together these fragments and continue to use the old names of physics, chemistry and biology. They learn by heart the surviving portions of the periodic table and recite as incantations some of the theorems of Euclid. But what they are doing is not science at all. For everything they do and say only makes sense within certain canons of consistency and coherence- which have been lost, perhaps irretrievably."

This is exactly what has occurred, argues MacIntyre, to our language of morality. I was quite skeptical at first, but his argument grows more and more compelling. He also includes a Who's Who of references to many of our PLS authors (Kant, Mill, Aquinas) -- and makes fun of almost all of them. In many ways, "After Virtue" is re-shaping a lot of my basic assumptions.

A later section decries the way that Philosophy and History have been divorced (Adam, this made me think of you, with your interest in the intersection of those disciplines):

"There ought not to be two histories, one of political and moral action and one of political and moral theorizing, because there were not two pasts, one populated only by actions, the other only by theories.

As a result of the separation between Philosophy and History, ideas are now endowed with a falsely independent life of their own on the one hand. Political and social action is presented as peculiarly mindless on the other."

I suggest that you read "After Virtue". If you have already read it, what do you think? I would like to discuss it once I finish. Perhaps over a beer. Come visit me in Philadelphia. All of you.

-LC

I've started a wonderful adult-education seminar at Chicago's Newberry Library on American Writers in Paris. This week we read passages from Gertrude Stein's The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Although ostensibly the autobiography of her companion, Alice B. Toklas, the book continues plenty of pithy insights into Stein's own fascinating life.

Stein was a pupil of William James at Radcliffe, and the two were very close. I loved the following passage, describing Stein's senior exam in William James' class:

It was a very lovely Spring day. Gertrude Stein had been going to the opera every night, and going to the opera also in the afternoon, and had been otherwise engrossed and it was the period of the final examinations, and there was the examination in William James's course. She sat down with the examination paper before her and she just could not. "Dear Professor James," she wrote at the top of her paper, "I am so sorry, but really I do not feel a bit like an examination paper in philosophy today." and left. The next day she had a postal card from William James saying, "Dear Miss Stein, I understand perfectly how you feel. I often feel like that myself." And underneath it he gave her the highest mark in his course.

I wish I'd had James as a professor.

-LC

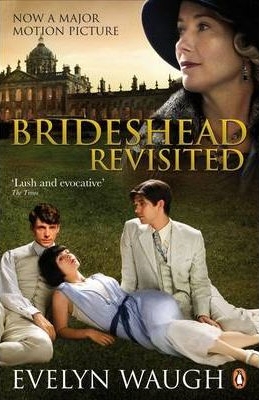

By Tess It's been a very Brideshead break for some of us. I reread it last week in conjunction with a friend who was new to it. Lillian, Joey and I started watching the 11-hour-long BBC miniseries over the weekend. That same day, Tavs texted us that - completely by chance - she was doing the same thing. What is the incredible appeal of Brideshead Revisited? Secular critics adore Brideshead, and it always ranks highly on lists of Catholic literature too. The well-known theologian Father Robert Barron even called it "the best Catholic novel of the twentieth century." Yet a lot of people I know really don't like it. Some find the characters intolerable, while another said that it left him "feeling tragic and empty inside." I concluded that in order to actually appreciate and enjoy Brideshead Revisited, it's not enough to simply plunge straight into it. The story is too tricky and subtle for that. I compiled this rather casual guide to approaching Brideshead Revisited for the benefit of a friend who wanted to read it, and in case anyone else would like to join in this unofficial little Brideshead book club, I decided to share it here too. 1. The first step is to set the scene for the chapters on Oxford, in the first half of the book. Do a little Google research on Oxford's Mercury Fountain and the Bullingdon Club for context. The Wikipedia pages are shockingly lacking in the juicy details, by the way. The Mercury Fountain has a small statue of the god Mercury in the center of it (no surprise) which the occasional Oxford undergraduate tries to pull down when inebriated. It has been pulled down three times, and legend has it that each man who got it down went on to become Prime Minister of England. Despite the threat of a heavy fine, Oxford students still regularly jump in Mercury when drunk and have a go at downing old Mercury. As the statue is now welded to its base, however, this feat is a lot more difficult than it was in years past, and I don't know anyone who has succeeded (although I do know someone who cut his foot on the pedestal while attempting to ensure his future career as Prime Minister. Shhh, don't tell!). Also, the Bullingdon Club is the most ridiculously exclusive group in British undergraduate life, and probably the world. Among other things, they are notorious for destroying restaurants/hotels/clubs that they party in. They leave the place an absolute wreck and then pay the damages, which as Wikipedia accurately notes, makes it "prohibitively expensive" to join. Of course, being in Bullingdon pretty much guarantees that you'll eventually become Mayor of London or Prime Minister of England. Members of the Bullingdon Club excel at getting into positions of power. They also excel at sitting around the place looking pensive in fabulous waistcoats. 2. Having set the scene for the Oxford portion of the novel, my next recommendation is to read the chapter on Brideshead Revisited in George Weigel's excellent book Letters to a Young Catholic (most of that chapter is available online). The chapter contains plot spoilers, but it offers a great philosophical explanation of Brideshead, so I recommend reading it first as a framework for understanding the book properly. 3. My final recommendation is about the way to approach the story. Ultimately, the main actor in Brideshead Revisited isn't actually any of the human characters; it's Divine Providence itself. The book is essentially an extended exploration of how God's grace works - slowly, subtly, and very strangely - on one dysfunctional British Catholic family. It's brilliant and beautiful, and completely imperceptible to non-Catholics, who will absurdly claim that the book is actually about the First World War or something similarly inconsequential to the plot. As a side note, if you can, try to read it slowly and really savor the language. Waugh wrote so beautifully! It blows me away sometimes. Even some tiny passages, such as the description of a certain wine drunk at dinner in Paris, are evocative, powerful, eloquent, haunting. What Waugh did with the English language was no small feat. I can only dream of someday writing half as well as he did. Finally, make sure you read the Epilogue, and especially the final few paragraphs. They gently convey the point and theme of the entire book. Anyway, a lot of people whose opinions I respect don't like Brideshead at all, and I can see that their criticisms are valid. It's certainly not for everyone. Perhaps, like me, you really won't like it the first time you read it. In that case, wait a few months, or even years, and try it again. It worked for me. Perhaps it will work for you too. And then, please come back and tell me what you think about it.

Has anyone else read The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo? I just finished it and was really struck by it. It's very well written (although I have a feeling it wasn't well translated) and the plot is so well wound I had no idea who the "bad guy" was until the author told me. Which is nice because with mysteries it's usually pretty easy to figure out. And the Lisbeth Salander character is one of the most interesting I've come across in a long time.

A warning; some of the content of this book is somewhat disturbing. There are some psycho sexual elements that are a bit off-putting. But they're supposed to be. That's what you get with a book titled "Men Who Hate Women," the original title . The American publishers changed it to make it more palatable for the American audience; a mistake since Men Who Hate Women is about as bombtastic a book title as I've ever seen.

Anyways it's a good read. Not a Great Book, but a pretty damn good one.

In other news you all should listen to a new band called The Civil Wars. It's just a guy on an acoustic guitar making beautiful music with a girl singing with him. Great harmonies, lovely voices and beautifully written songs. Check 'em out.

So I've had lots of time to read lately, and here's my list (feel free to comment on the order I should arrange them): - Marcel Proust - Swann's Way- G.K. Chesterton - Everlasting Man (can't believe I haven't yet read this) - C.S. Lewis - Screwtape Letters- Rainer Maria Rilke - Colllected Poetry - Matthew B. Crawford - Shop Class as Soul Craft- Josef Pieper - Leisure: The Basis of Culture (rereading because it's that good)

Any suggestions?

I'm also watching a lot of films, and I HIGHLY recommend Zach Braff's The High Cost of Living. I kind of fell in love with him -- surprising? no -- through "Scrubs" and Garden State and I had heard good things about this movie. It's got a really weird plot, but I think brings to light certain issues, kind of like Juno. All pro-life people will like it, or at least support its message.

In terms of music, I've gotten into a lot of house lately (Avicii, Skrillex, and of course deadmau5), as well as continuing my Mumford & Sons obsession (when was their new album supposed to come out again?), Josh Ritter (thanks, Jack), and checking out Bon Iver's and Coldplay's new albums. Also whenever "Without You" (David Guetta ft. Usher) comes on the radio I shamelessly blast it with the windows down...such a good pump-up pregame song. I recommend for the sentimental ones among you Alex Murdoch, whom I started listening to after watching the truly terrible film Away We Go with John Krasinski. Even Jim Halpert couldn't rescue that one.

Lots of love,

Tavs

Hey Team, I don't know if any of you have seen this but I thought it was worth perusing. I was on the PLS website looking for books to add to my Christmas list (since I didn't buy most of our reading list myself thanks to Hesburgh and the PLS libraries) and stumbled on this little item. It's a series of short essays written by PLS alums about how PLS has benefited them over the years. There's nothing new or mind-blowing here, but it was a nice reminder of why I chose PLS and what I hope it can do for me in the future. I've noticed several posts in our forum about how, as recent grads, it's a little difficult to reconcile our PLS mindset with life in the "real world." Maybe this will help. Cheers.

I started to read it late Saturday night, as a bid to summon sleep. I ended up staying awake later than I have in weeks to finish it. I can't quite believe that I made it through 22 years and the full gamut of American education without ever reading The Outsiders. It was short, simple, occasionally wrenching but sweet. I know that S. E. Hinton's well-drawn characters and relatable but not heavy-handed message will become part of my lexicon, as other beloved books have.

Best of all, I felt a glowing pride that I think I- we- have "stayed gold," as Ponyboy's friend admonishes towards the end of the novel. It may sound cheesy and trite, but- we watch sunsets. I hope we always will.

I know others must have read The Outsiders, maybe years ago (I liked the book now, but I think I would have found it really timely had I read it at 17). What characters do you love? Which parts do you hate? Who, in the end, was truly gallant?

Stay gold,

LC

Dear Friends,

A friend of mine gave me a book lately. It was a new edition of Emily Dickinson’s letters, just recently out. The volume itself is rather pretty, with old-fashioned flowers sprouting on the front - and just the right smallish size a book ought to be, easy to take anywhere. While I always feel a little bad snooping into dead people’s letters, I thought I’d give it a try.

I’m glad I did – it’s delightful. I’ve always been a fan of prose more than poetry, so I love learning about Emily Dickinson and seeing her style through her sentences rather than verses. If you have read her poems, her letters give insight into the mind behind them; if you’ve never read her poems, the letters open a window to such an interesting personality, with so many quietly compelling beliefs and ideas.

It seems like whenever I pick up the volume I find some very PLS-y quote that is beautiful and wise and makes me think. It certainly makes me wish my own letters were more eloquent and insightful than they usually are. :) The things Dickinson says about writing, about living, about friendship, are so uniquely and gorgeously expressed. Here are just a few to whet your appetite:

“It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sundowns sterner…November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.”

“Of our greatest acts we are ignorant.”

“I think you would like the chestnut-tree I met in my walk. It hit my notice suddenly, and I thought the skies were in blossom.” (Martin Buber anyone? ;) )

“You speak of ‘disillusion.’ That is one of the few subjects on which I am an infidel. Life is so strong a vision, not one of it shall fail.”

"A letter always feels to me like Immortality because it is the mind alone without corporeal friend. Indebted in our talk to attitude and accent, there seems to be a spectral power in thought that walks alone..."

It’s funny that Emily Dickinson seemed to live such a quiet and retired life, but the life you see in her letters is very vibrant, her world very full.

That’s what I loved most about these letters – how Emily D. is so in love with living. And, for her, to truly live isn’t to have power or to have knowledge or to be great – it’s just to feel the world around you, to be left breathless by its beauty. Even her poetry - she doesn’t write for the sake of leaving some grand legacy, she writes because it’s a channel to express her joy at living. She says that “when a sudden light on orchards, or a new fashion in the wind troubled my attention, I felt a palsy, here, the verses just relieve.”

Love from, Emily W.

The Intellectual Life by A. D. Sertillanges, O. P.

Foreward by James V. Schall

The intellectual life is a vocation that is “not fulfilled by vague reading and a few scattered writings” (Sertillanges). This book asks the question, “how do I go about knowing?”

Though St. Thomas Aquinas did not have a computer or typewriter, he developed a great memory and ability to have at his fingertips the knowledge of the great writers before him, including Scripture [He knew Scripture by heart, actually]. Even for St. Thomas, this wisdom took books and reading.

Sertillanges thinks that a true intellectual life is possible if we keep one or two hours a day for serious pursuit of higher things. He advises those who wish to have an intellectual life to “begin by creating within you a zone of silence.” We find the time by longing to know. Sertillanges “demands an examination of conscience both about our sins and about our use of our time” (xii).

What we call intellectuals are not what Sertillanges had in mind. These “intellectuals” “may well be evolving theories and explanations precisely as a product of their own internal moral disorders” (xii). The intellectual life is dangerous; the greatest vices stem from the spirit, and there is an intimate connection between knowing the truth and not ordering our souls to the good.

This book is a practical handbook of the habitual concern to pursue the truth. “This is a book that allows us to be free and independent, to know, and to know why we need not be dependent on the media or ideology that often dominate our scene.” It teaches us how to go about knowing. This book will affect our lives. “It will make us alive in that inner, curious, delightful way that is connoted by the words... The Intellectual Life” (xiv).

Translator’s Note by Mary Ryan

All intellectual workers will find suggestion here, perhaps in the central conception that “our every effort to reach reality is an approach to the great primal Truth” (xv), perhaps in the notion of individual vocation, perhaps of work “in joy”, perhaps in the detailed help to living by certain principles.

Preface by Sertillanges

This book comes straight from what his heart had pondered for many years. He has received many letters, some for the technical help, some for the ardor stirred, some for the revelation of “the spiritual climate proper to the awakening of the thinker” (xvii).

He counsels the aspiring intellectual to begin by creating a “zone of silence” which is a habit of recollection, a will to renunciation, and a detachment devoted to work. It is a state of soul without desire and self-will. [What of the desire for truth? I think he means without the lower passions].

When the thinker thinks well, he follows God his creator step by step. Research is akin to Jacob’s wrestling match with the angel. Given these conditions, it is not natural for the thinker to throw off his fellow everyday man, with all his impediments to the True. Rather, the intellectual must always be ready to “take in a part of the truth conveyed to him by the universe, and prepared for him... by Providence” in a “miraculous encounter” (xix).

Intellectual work begins with ectasy, “a flight upwards, away from self, a forgetting to live our own poor life, in order that the object of our delight may live in our thought and in our heart” (xix). Memory has a role; especially the memory that is receptive and perpetually discovering.

Our true being, our authentic self, lies in the “creative Thought”, the truth of our eternity that is revealed to us in the silence of the soul. This silence excludes foolish and distracting thoughts, and represses the “murmured suggestions that our disordered passions never weary of uttering” (xxi). The eternally true is “far from the covetous and passionate self” (xxi) [Giussani might take issue].

Great men, though they seem bold, are more obedient than others. They hear the sovereign voice. We must learn our own littleness by looking at their greatness, and then set the aim of our life within the scope of our grandeur.

Sertillanges advises to work far from the world, “as indifferent to its judgments as you are ready to serve it” (xxiii). We must be wary of disparaging, envying, unjustly criticizing, and disputing with others, which are incompatible with devotion to eternal truth. We should be glad at the superiority of others. We should not bend to the vulgarity of the commonplace. We should be severe with ourself and love the truth even when we are guilty of violating it. In addition to admitting error, we must uncompromisingly adhere to our fundamental persuasions, the “supreme certainties... on which all the work of the intelligence rests” (xxvi).

We shall correct excessive widening of the field and hastiness by a greater devotion to the true. We shall examine antecedents and connections with other subjects before narrowing down to a particular subject. We shall take refuge in creation and the idea from which it comes. Failures prepare for future successes. If reason submits to eternal truth, it will recognize its own limits and the the value of faith.

Foreward by Chandolin

He mentions a letter of St. Thomas Aquinas to a Brother John, in which are enumerated “Sixteen Precepts for Aquiring the Treasure of Knowledge” (xxix).

Chapter 1 The Intellectual Vocation

I. The Intellectual Has a Sacred Call

Vocation refers to those who intend to make intellectual work their life, whether they are entirely free to do it, or only can do it with reserve time. Fulfilling this vocation requires more than vague readings and scattered writings; it requires “penetration and continuity and methodical effort”; it is deep.

One sign that one has this vocation is that one has or is consolidating “from the foundations upwards a sum of knowledge recognized as merely provisional, seen to be simply and solely a starting-point” (4). A vocation is not asked for, but it comes from heaven and from our “first nature”; we are to be docile to God and to oneself once they haves spoken. Pleasure can reveal our vocation, if we search deep down where our liking and impulse are linked up with God’s gifts and providence.

We must come to the intellectual life unselfishly. We must accept the end and the means of the vocation. We must ask persistently for knowledge. We must “will what truth wills... organize [our] li[ves] and... learn from the experience of others.

Those who devote only a portion to intellectual life must be especially devoted during that portion. The isolated man, if he have a heart, may be in a better place than the man in a city. The most valuable thing is a will for an ideal. An impassioned solitude is better than life in public.

Sertillanges says to those aspiring intellectuals that they need only two hours a day. He asks if we want to have “a humble share in perpetuating wisdom among men, in gathering up the inheritance of the ages... in turning men’s wandering eyes towards first causes and their hearts towards supreme ends... in organizing the propaganda of truth and goodness”.

II.The Intellectual Does Not Stand Alone

The Christian worker is not isolated. Though solitude is life-giving, isolation is sterilizing and paralyzing. It is inhuman. “A true Christian will have ever before his eyes the image of the globe, on which the Cross is planted, on which needy men wander and suffer, all over which the redeeming Blood, in numberless streams, flows to meet them” (13). All truths are practical, are life and a way to the end of man.

We should then work with some idea of utilization. We should listen to the needs of the human race about us [take note, Pat]; we should “find out what may bring them out of their night and ennoble them; what... may save them” (13). We should seek redeeming truths. “Jesus Christ needs our minds for His work” (13).

III. The Intellectual Belongs to His Time

While every moment of history is important, the time in which we live is the most important for us. Let us help God renew the face of the earthT

Chapter 2 - The Virtues of a Catholic Intellectual

I. The Common Virtues

Virtue leads to an intellectual end [“Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God”], so virtue is equivalent to the supreme knowledge. Superiority in any branch of life includes a spiritual superiority. It is not right to be in close contact with “the great spring of all things” without becoming like it morally. Life is a unity; we must give play to all its functions. The source of life’s unity is love; love is common to knowledge and practice. “Trust visits those who love her, who surrender to her...with...virtue.” The roots of the true and good communicate. “By practicing the truth that we know, we merit the truth that we do not yet know” (19). Virtue is the health of the soul, and health affects sight. “It is not the mind alone that thinks, but the man” (20). A heart ravaged by vice, passion, and guilty love cannot think rightly. “Purity of thought requires purity of soul” (22). St. Thomas says that the virtues by which the passions are checked are of great importance for acquiring knowledge. Sertillanges holds that “passions and vices relax attention, scatter it, lead it astray; and they injure the judgment” (21) [contrast to Giussani]. “To calm our passions is to awaken in ourselves the sense of the universal” (21). Besides lack of intelligence, the various sins are the enemies of knowledge. Without them, a man of study will reach his destiny. When we speak of the good as the Supreme Spring at the summit of which the true is the good, the good spoken of is the desireable good; but moral good “is nothing else than desireable good measured by reason and set before the will as an end.” We approach truth through the universal, which is both the true and the good. Think of pursing truth like ascending a Great Pyramid; if you go up by the Northern edge (truth), you get nearer the southern edge (goodness).

II. The Intellectual Virtues

The virtue proper to the man of study is studiousness, but this includes many things. St. Thomas placed it under temperance - we must temper our thirst for knowing and adapt it to circumstances and duties. Two vices are opposed to studiousness: negligence and vain curiosity. Vain curiosity can creep in “under cover of our best instincts” and ruin them. Ambition can hinder studies. Study is not always opportune; we must sometimes do our duty as a man or as a professional. St. Thomas reminds us, “do not seek what is beyond your reach” (27) and to “go to the sea by the streams, not directly” (27). Before building an intellectual structure, we must examine the base, the beginning. We must know our “intellectual substructure” and start small to see things grow big. We must not overestimate ourselves, but judge of our capacity so as to accept ourselves as we are and thus obey God.

Furthermore, study must leave room for worship, prayer, and meditation on the things of God. Though study is indirectly divine because it seeks out and honors the traces of the Creator or His images as it investigates nature or humanity, it must make way at the right moment for direct intercourse with God. We must not give up prayer, recollection, reading Scripture and the words of the saints; we must not neglect the Divine Dweller within us. Since in reality everything depends on the divine, so too should it be in the effigy of the real within us.

III. The Spirit of Prayer

Besides prayers before our study, we should also cultivate a spirit of prayer within our study. We do this by seeing every truth in relation to the absolute Truth; every particular truth is a symbol, a meeting-place where we meet the “sovereign Thought” (31). The fact that eternal Truth is in every instance of truth should lead to a heavenly ecstasy. In Christian knowledge we take a step towards God and return with the gifts of the prophet. The right mind answers “God!” to all questions whatever the particular answers are. We should pass from the trace or image to God, and then come back with new vigor and strength to “retrace the footsteps of the divine Walker” (33). We find new meaning in things, a spiritual happening. We study eternity.

IV. The Discipline of the Body

We cannot separate spiritual functions from corporeal ones. According to St. Thomas, the dispositions of soul depend on the dispositions of body; a noble soul corresponds to a good bodily constitution. We can communicate and receive thought and knowledge only through the body. Two considerations must be made. First, we should endeavor to keep well. This endeavor should include good hygiene, open air, stretching and breathing, daily exercise, possibly some manual labor, about 2 vacations a year, a light diet, exactly how much sleep I need, etc. For the intellectual, care of the body - the instrument of the soul - is virtue and wisdom. Second, vices such as laziness, gluttony, and other indulgences in pleasure are to be avoided. Mortification of the senses is necessary for clear thought and vision. We are to be “an intelligence served by organs” (40).

Chapter 3 - The Organization of Life

I. Simplification

In order that everything in me should be directed towards my work, I should arrange both my interior and exterior lives. Firstly, I must simplify my life. Asceticism must be applied to cut away from life most of the noisy and spadmodic interruptions, and the burdens of an excessively comfortable life. Artificial society life is not for a worker. Be dictated by conviction, not custom. Money and attention is better spent on collecting a library, providing for instructive travel or restful holidays, hearing inspiring music, etc than on trifles. One does not write and think for money, though one might make a living that way.

The wife of an intellectual has a certain mission. She should be Beatrix, not a spendthrift and chatterbox. She should espouse the career of her husband and not draw his thought down from the heights. The married man should draw strength, inspiration, and ideals from his wife and children. A woman can do much to help a man in his studies; she can mother him after he is wounded by his work. Children should be a cause for joy and a motive for hope: “You can see an image of God and a sign of our immortal destiny in this image of the future” (46). Those who have renounced family life in order to devote themselves to their work and to God who inspires it have cause to rejoice and to say of others, “There is one snare that he did not succeed in avoiding, marriage” (46).

II. Solitude

We must organize our lives so as to preserve exterior and interior solitude. St. Thomas directs 7 of his 16 counsels to the intellectual towards this end (see p 46). We must practice retirement, of which the monastic cell is the symbol. Silence watches over prayer and work. Sertillanges describes the conditions of quiet recollection and of being the Spouse of truth (in the winecellar) in detail. These conditions include being slow to speak and slow to go to places where people speak, frequenting only a few who society is profitable, avoiding excessive familiarity, ignoring purposeless news and the doings of the world that do not have intellectual or moral bearing, avoiding useless comings and goings. All great men, including Jesus, entered solitude, aka the desert, aka retirement, aka “the night”, aka the “vast emptiness which is plenitude” (48). The things that count must barricade the things that don’t. “Did you not prefer truth to the daily lie of a scattered life, or even to the noble but secondary preoccupations of action?” (49). Solitude allows us to bring materials together, to create, to work. It also enables us to know ourselves and to be the prophet of the God within us. A crowd causes us to lose our self: dispersed and scattered, we answer “Legion” to “what is thy name?” (51). Sertillanges prescribes for the soul the bath of silence. Though one cannot contemplate all the time, one directs all other action towards contemplation, making a sort of continuity (as much as possible on earth). The pleasure of contemplation helps us. For the intellectual, my neighbor is the person who needs the truth. Jesus shows us that one can be entirely recollected in God and entirely devoted to others.

III. Cooperation with one’s fellows

The solitude we have spoken of needs to be completed by other values. We should seek to further the higher contacts of our retirement by consorting with well-chosen associates. What a wealth could be had, what a labour could be saved, if intellectuals helped each other and even lived together! The support of others is an efficacious defense against the gloomy mood that strikes us when we work alone. In monasteries, each room is the scene of assiduous work encouraging the others, and their rare interactions of cooperation are marvellous. “Friendship is an obstetric art; it draws out our richest and deepest resources; it unfolds the wings of our dreams and hidden indeterminate thoughts; it serves as a check on our judgments, tries out our new ideas, keeps up our ardor, and inflames our enthusiasm” (56). We should try to join some group where men of understanding assume a task and devote themselves to an idea. Even if materially isolated, we should seek to join in spirit with the friends of the true, with all seekers, and especially with the Communion of Saints. Unanimity which bears fruit consists mostly in this: “that each one should labor with the feeling that others are also are labouring, that each one in his place should concentrate on the work while others also are concentrating” (57).

IV. Cultivation of Necessary Contacts

It is our task to link necessary contacts with our intellectual life, so that they serve it. But the man, the true self is more important than our work; if our human perfection requires it, it will help our intellectual life, for the good is brother to the true. To do what we ought disposes us for contemplation, it is “leaving God for God”, says St. Bernard. There is something to be gleaned from every interaction, and we must always keep the sense of the common life, the sense of the human lot. In all of the real we can find much to learn, especially by making comparisons with man, the center of all things. We should seek to associate with superior minds, but even fools (who we need not seek) have their place in completing our experience. Since our intelligence is partnered with our other faculties, we should adjust these component parts and turn even the body’s weak points such as illness into things of value “by means of some happily ingenious greatness of soul” (60). Still, in associating with others, its best to keep our mind and heart in control, and to interact as if we were an angel. We should moderate our speech, so that we keep possession of ourselves and give weight to our words.

V. Safeguarding the Necessary Element of Action

We must find the right balance between silence and sound, interior and exterior life. While the contemplative and intellectual life is the contrary of action, and we should praise what we do not do, but real life does not allow such a strict separation. Action prepares conscience for the rules of truth. There are physiological and psychological reasons why we need some action. In addition, St. Thomas notes that we need to anchor ourselves in the real, which is the ultimate goal of judgement. True thought bases itself on facts. The element of action will steady and enrich the mind, testing and illustrating our ideas. The individual is the real, as opposed to the themes of the mind. Besides providing experience, action also teaches energy; it stimulates us and shakes us out of laziness. Sertillanges recommends that the man of study steadily devote himself in some active, productive, useful enterprise in which he could dedicate a definite amount of time. Taking a break from inspiration will make her lovelier upon return.

VI. Preservation of Interior Silence

It is in view of necessary silence, retirement, and inner solitude that action and other contacts are admissible and regulated. Therefore the spirit of silence must pervade all of life. An intellectual must be a full-time intellectual. For him the true is the glory of God that must be pursued in everything. His solitude is not so much of place as of recollection, rising above things rather than keeping away from them. “Purity of solitude” may be maintained everywhere.

Chapter 4 - The Time of Work

I. Continuity of work

Let us consider the time a thinker devotes to intellectual work. Study is a prayer to truth, and we ought to pray always (Luke 18:1). Prayer is the expression of desire, and so to say we ought to always pray is to say “we must always desire eternal things, the temporal things which serve the eternal, our daily bread of every kind and for every need, life in all its fulness earthly and heavenly” (70). It is the thinker’s special characteristic that he is obsessed with the desire to know, and keeps it churning at all times. Truth is everywhere, not just in the concentrated hours of study, and so we must learn to look and make comparisons between what we see and our familiar or secret ideas. “A thinker is like a filter, in which truths as they pass through leave their best substance behind” (74). He keeps all his life the curiosity of childhood. Observations should contribute to our general knowledge and culture and also to our speciality. We should keep a part of our thought expectant; we are to live in the presence of Truth, the special divinity of the thinker. We must only train our minds a little and they will follow a new law. Our search should not be tiring, but as play. Also, we should of course pay attention to men [like Fr. Klamut] who think and know.

II. The Work of Night

We must make night work for us. When we sleep, our will relaxes and lays down its function to be nearer to nature, we surrender. We should not keep awake, or compromise sleep, but we should make it work to our advantage. Brain-work started develops during the night; connections are made. Sometimes the collaboration of sleep is apparent as soon as we wake, but more often we have to glean it out of sleepless moments. Rather than entrusting insights we have at these times to the relaxed brain, have a notebook or paper slips ready to record them without even turning on the light (when they occur in the middle of the night). This will help us sleep. Early morning lucidity should be recorded and waited on. We can prepare for sleep as monks do, sowing the point of meditation for tomorrow in the evening - or in our case, sowing the seed of our work (we can do both). As I fall asleep I should call to mind my preoccupying question or developing idea, entrusting them to God and my own soul; but sleep should not be delayed.

III. Mornings and Evenings

If we are to “prepare, supervise, and end” the night attentively, we must not leave the hours surrounding it to chance. The morning is sacred. We view our destiny, we confirm our vocation, and set out on a new stage of our journey. If possible, the morning should hold the combined effort of waking with a voiced prayer formula, morning prayer (liturgical), and Mass. In the morning the child of truth must give himself to truth, and can profit by the common and simple acts of faith (in truths at foundation of knowledge), hope (that God will bring light), and love (for Him and for those whom our study aims to bring nearer Him), as well as by the Our Father (asking for the food of our intelligence) and Hail Mary (to her who conquers errror). Mass connects us with humanity, the universal Church, and our mission.

Evenings must be made holy and quiet in preparation for a really restorative sleep. An intellectual’s evening should be a time of stillness, his supper a light refection, his play the task of setting the day’s work in order and preparing the morrow’s. He needs Compline. We must prepare the night which links our toil. Rest is not found in seeking pleasure, but in “giving up all effort and withdrawing towards the fount of life” (92). It means restoring not expending. Sport and recreation should not normally be done in the evening. In the evening we are to cease willing up to a point so that the renunciation of the night may begin.

IV. The Moments of Plenitude

This section describes securing the moments of intense concentration and guarding them against all intrusion. We should study ourselves and decide when these hours will be, but if all is free then the morning seems best - however, you may have certain complications to the morning. During this time, do something with all my might, then invite inspiration. Most estimate that 2 to 6 hours is all that can be profitable, but some work more. The use and mind, not the number of hours, is important. We MUST preserve solitude during this time, but not necessarily solitude of place - another’s presence might help us to work. Except in obvious cases, we should not even allow our solitude to be broken by charity, for our service of truth is charity. Endeavor to win the affections of those hurt by our solitude, but it should be more desireable for them if we retire than if we stay in their company.

Chapter 5 - The field of work

I. Comparative study

What should be studied is a matter of personal vocation, but we can give a starting point. We are talking to those who have left school and propose to go deeper. Comparative study is widening our special work by bringing it into contact with all its links, especially to philosophy and theology. Knowledge is a human habitation and so must be acquainted with everything human. We must correct for the harmful effects of certain branches of knowledge by studying other branches. We should approach the center of all ideas by trying different paths which, like the radii of a circle, seem to converge on a common meetingplace. Very great men are universal. Choose your advisers well. Our time needs harmony. We can introduce order into our knowledge buy an appeal to principles of order - by philosophizing, and crowning philosophy with a “concise but profound” theology. Theology can be learned by devoting four hours a week for 5 or 6 years. Beware above all of false teachers. Go straight to Thomas Aquinas. Take the time to learn his Latin. Consider reading a book that introduces his thought. Consider getting a tutor, but when in doubt go straight to Aquinas.

II. Thomism, the Ideal Framework for Knowledge

Thomism is the ideal framework of comparative study. It gives “a body of directive ideas forming a whole and capable, like the magnet, of attracting and subordinating to itself all our knowledge” (114). Our age is misfortunate in that she lacks a coherent system of ideas; we would benefit to escape this misfortune by a sure body of doctrine such as Thomism. Sertillanges insists that Thomas is the man for our day. He praises many attributes of Thomism, such as its juncture at faith and reason, its reconciliation of adjacent systems, its being the logical end of every point of knowledge, its ability to adapt to new knowledge, and finally its endorsement by the Church as “an ark of salvation, capable of keeping minds afloat in the deluge of doctrine” (117), although it has its errors. He encourages “willing and filial loyalty” (117) to Thomism.

III. Our Specialization

What we said about comparative study must be tempered lest it thought that encyclopedic knowledge is the goal. Given the conditions of reality, such broad knowledge can be a hindrance to true knowledge, i.e. scientia - deep knowledge through causes. We must sacrifice extent for penetration, and once we have attained a basic formation in all disciplines then we must move on to specialization. For firstly, we are more capable of and suited to researching a certain subject, and we should want to work with joy. Furthermore, minds that are too spread out run the risk of being too easily satisfied. Going broad helps us to become cultivated and superior men, but specialization gives us a useful function; comparative study helps us understand, specialization helps us do.

IV. Necessary Sacrifices

We cannot do everything, so we cast a glance of sympathy to what we cannot do, and do what we can; know what we have resolved to know, leave what does not belong to our vocation to God. “Do not be a deserter from yourself, through wanting to substitute yourself for all others” (122). We do it all anyway through our God and our brethren with whom we are united in love.

Chapter 6 - The Spirit of Work

I. Ardor in Research

We need a spirit of earnestness. We seek particular truths that are the representatives of that Truth to which we have committed our service. Our intelligence ought to be like a child who never ceases to ask why? We must cast aside laziness and continue full speed ahead, or like a plane we crash. We must always seek to know more and be consumed with zeal for truth. We must have an inspirational, a heroic instinct of the conquerer. “Infinity, lying before us, demands infinity in our desire, to correct as far as may be the gradual failure of our powers” (127).

II. Concentration

The spirit of earnestness must be coupled with a habit of concentration. Our mind should become a lense, wholly intent on whatever is the dominant idea, with all our powers to bear on the point chosen to concentrate on. We should also order our studies and throw ourselves into each one serially as if it were the only one. Work in connection with one subject must be strictly disciplined in one direction. This will help us to navigate confusing masses of info and to discover essential connections, the secret of great works. Worth lies in the relationship of a few elements which govern the whole subject, revealing the underlying law and enabling original creation.

III. Submission to Truth.

Submission and prompt obedience to truth invites it to visit us. To yield to (worship) truth, we need to be humble and to empty ourselves of self-will. Good study is “God becoming conscious in us of His work” (131). Let us not obstruct Him. Passivity and receptivity are key. Too anxious activity prevents us from going outside ourselves to the object of truth, while we want a state of ecstasy- “to lose oneself in [truth], not to think that one is thinking, nor that one exists, nor that anything in the world exists but truth itself” (133). Still, the intelligence is active (though deliberation should be delayed) as the love for truth transports us into the universal. Divine inspiration is much more profitiable than merely abstract thoughts. We ought to abandon ourselves to and obey God. Still, inspiration or good things may comes from unexpected sources; do not consider the person speaking but the truth said. In humility, consider others better than ourselves and we will learn from them, especially if they are teaching, which is a sign of Christ.

IV. Breadth of Outlook

In addition to earnestness, concentration, and submission, we must make an effort at breadth which gives each study a kind of universal bearing. If we do not see what we have analyzed by some specific method as a part of the whole, we falsify truth. The Truth is a single whole, and man’s mind is a unity, not satisfactorily formed with broken fragments of the true and beautiful. Truly studying a thing invokes all other things. Concentration and and “looking abroad” cooperate, as do losing unity by lingering on details and unifying details in a comprehensive synthesis. We must think high and rise above our academic rules. “The ideal would be to establish in one’s mind a common life of thoughts all interconnected and forming, as it were, only one. So it is in God” (140). We are to take God’s point of view to find cohesion. Research’s soul is the “feeling for the infinite”, which is disappointed without reverberations outside itself. Study the spirit, not the letter.

V. The Sense of Mystery

Even after our maximum effort and after truth smiles on us, the sense of mystery must remain. God poses the questions; only God can answer, and God is infinite. “We do not know all of anything” says Pascal (141). Only the petty man believes he possesses the cosmos and what it contains. St. Thomas - “All that I have written seems to me but straw” (142). Awe of the mystery corrects misleading pride, and distant lights incite us to work on. The visible relations of things have their roots in the night into which we are groping; we are not “consigning [what we achieve] to darkness; for it is the light we do not see that best sustains the dim reflections of our astral night” (143). [I’m not sure about this “night” - I thought we were “Children of the light” (1 Thess 5:5)].

Chapter 7: Preparation for Work

I. Not Reading Much

We must know how to read. The first rule is to read little (compared to the amount of writing the floods libraries and our minds). The passion for reading is, like other passions, a hindrance and disturbance to the soul. Instead of reading passionately, we must read intelligently. Too much reading dulls the mind and prevents our intelligence from fulfilling its true function. [PLSers are doomed]. It is much better to preserve self-control and manage our brain prudently. Remember to take recreation out of doors. Do not ignore the human race, but do not be swept away with its current. Rarely read novels and for news a weekly or bimonthly chronicle should suffice (besides for remarkable articles or grave events). “Never read when you can reflect; read only, except in moments of recreation, what concerns the purpose you are pursuing; and read little, so as not to eat up your interior silence” (149).

II. Choosing Well

We should be concerned about the seeds of our thoughts, which can lead to salvation or ruin under the influence of God and the devil. Sertillanges recommends going straight to the first-rate thinkers, especially original thinkers. Take note of growing, present notions, but take your stand on the permanent stock of old ideas and eternal truths in eternal books. It is also necessary to choose within books. For example, sometimes we must filter out an author’s ignorance or concupiscence. But an intelligent man finds intelligence everywhere. “Try to secure that all shall be good, wide, attuned to truth, prudent, and progressive” (152).

III. Four kinds of reading

Sertillanges distinguishes between fundamental reading (reading for formation and to become someone), accidental reading (in view of a particular task), stimulating or edifying reading (to acquire a habit of work and the love of what is good), and recreative reading (for relaxation). Each has a virtue: fundamental reading requires docility, accidental - mental mastery, stimulating - earnestness, recreative - liberty. When being formed, it is best to believe our masters - to accept an attitude of “respect, confidence, faith” until we form all the elements of judgment. One should solemnly choose three or four authors for one’s speciality, and three or four for each problem that arises. Other books are consulted for information, not formation. The person who seeks information to use is not purely receptive. That is, study and consultation differ. Stimulating reading depends on each one’s experience, but you may have a favorite author or passage that your return to again and again as a source of invigoration. Reading for relaxation should be joyful; we should like it but it should not excite us too much or harm us in any way. These books should help develop our personality, mind, and manhood.

IV. Contact with writers of genius

We should prepare for contact with genius as we would prepare for meeting a saint. Contact with genius gives us the joy of being a man, of talking with the greats, of having a Godly society. On pp158 he lists several geniuses of literature, philosophy, science, and religion. Cultivating admiration for these men and women helps us to be our best self. They draw us up into their atmosphere and introduce us to the Spirit, the first author of all one writes. What a man of genius expresses is humanity. His articulate expressions help our stammerings. Of special importance are those great men who sum up the thought of generations in their persons. Through geniuses we grow and all things are made new for us, i.e. in a new connected system. Genius tears aside the veil of the depths of thought behind every fact. Genius simplifies. Genius stirs us to confidence in a vocation. Even the errors of great men can lead to our progress, through the Providence of God. Think of what the Church owes to heresies!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed